TuBlog |

|

Practice, Progress, Performance

TuBlog |

|

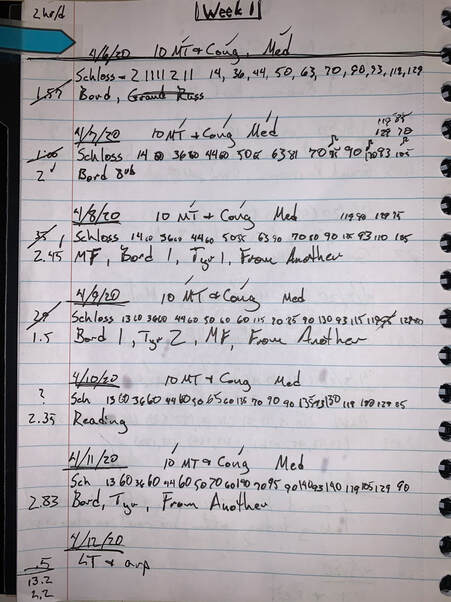

I've mentioned in past posts that I keep a practice journal. There are many benefits to practice journaling. You can see the progress you're making, you can look at what you've been spending the most time working on, it makes it easier to plan what to work on, it makes it easier to diagnose problems with fatigue, and the list goes on. I recommend that all my students keep a practice journal. For this post I've included pictures of my practice journal in the three main sections in it. I'll go over exactly what I keep track of in each section and the various elements of each. Section 1: Daily Log In section 1 I keep track of the things I do in my daily practice sessions. There are several elements I like to track from one day to the next:

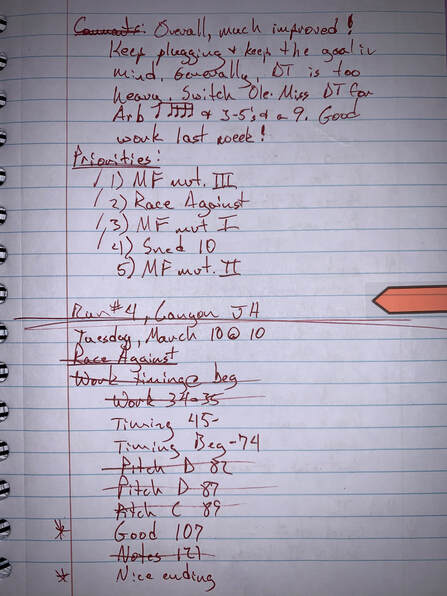

Section 2: Listening Commentary Any time I do a run-through I record it, listen back to it, and take notes over what I hear. It's a great way to teach yourself! The picture here is of the last page of the commentary for my third run-through and the first page for the commentary from my fourth run-through. I'll go over this page from top to bottom.

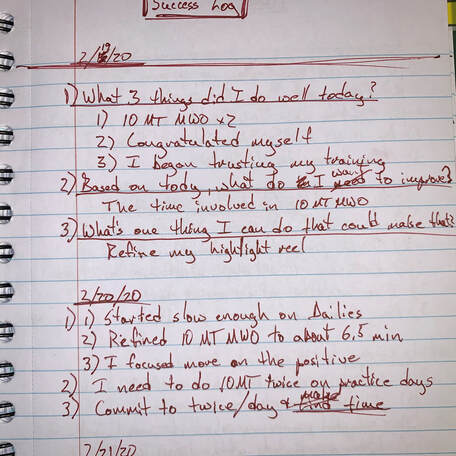

Section 3: Success Log The Success Log is something I started doing recently. It's a great way to end a practice session on a positive note. It's pretty simple, but often not as easy as it seems it should be. It's also pretty self-explanatory.

I experimented at one point with using an Excel spreadsheet, but there's just something I like about having a handwritten journal that I enjoy more than tracking in a spreadsheet. Using some form of electronic journal is fine as long as it works for you. I like that I can hold my journal in my hands and that it's ready to accept or display data as soon as I pick it up, no searching necessary. As I mentioned above, there are many benefits to using a journal. You can use as many or as few of the elements I listed. Journaling is a great way to make your practice more effective, efficient, and deliberate. Happy journaling!

1 Comment

When brass players attempt to think about the way to move their body as they play, they become overwhelmed in trying to consciously control the cripplingly complex entity that is the human body. This is known as paralysis by analysis and is documented as far back as Aesop's Fables. Try this: describe, in detail, every single body movement required to shoot a basketball through a basketball hoop. Or, try to shoot a basket by thinking of each step involved.

Here's a taste of the complexity involved in such an action. First, you have to jump. How do you jump? You forcefully extend your legs. How do you do that? You have to contract your quadriceps, glutes, and calf muscles. Awesome, how do you do that? You have to send a signal from your brain along the specific nerve pathway to the appropriate muscle group...? Sweet, so you know how to consciously send signals through your nerves? No. Oh, okay. The point is, at some point along the way you would have to delve into areas that only the subconscious mind is capable of controlling. The same is true for playing an instrument. So many players, myself included, get caught up in forcing our bodies to work in a way that it isn't inclined to do. We try to consciously control the physical aspects of our performance. We have almost no business in doing so. The single exception I can think of in this case is incorporating a new movement pattern in place of one that is limiting your progress as a performer. I recently came to the realization that this was happening to me as I would play a specific interval during my daily routine. As I attempted to play the interval, I'd think about how to form my embouchure or how to shift. Inevitably, I'd miss the top note of the ascending interval. Then I'd repeat the process of playing the interval until I played it accurately a few times. This cycle repeated itself every day over the course of months or years. I'd try different things at different times. I'd sing, buzz, and then play. I'd transpose the interval to a different range higher and lower. Really the only thing I've found that works reliably is focusing on the sound I want to produce, rather than the exact movement required to produce it. For someone who's been playing a brass instrument this is similar to a movement cue. Movement cues are simple instructions which inspire a specific result in the body. Here's my favorite. When I was learning to squat I had trouble increasing the weight I was lifting beyond a certain point due to lower back pain. My trainer told me that I just needed to engage my hip-rotators. At the time, I had no idea what she meant by "hip-rotators" nor how I was supposed to engage them. Basically, the hip-rotators are a group of muscles around the hip joint that help control how the femur moves and helps protect the spine as you squat with weight on your back. The second trainer had a great movement cue for engaging the hip-rotators: spread the floor apart with your feet as you squat and stand back up. Try it! Put your hands on your hips and try to spread your feet apart. You don't even have to squat to do it. The muscles that flex as you do this are the hip-rotators! You didn't have to think about it at all. You just spread the floor with your feet. That is an effective movement cue. Now, a similar phenomenon needs to happen when you play your instrument. Think of the result you want to achieve, not how to achieve it. You want to play an interval? Hear the interval in your head as clearly as possible as you try to play it. You could even imagine your favorite player and how they would play it. Doing this gets you out of your own way. Here's another example. Say your name out loud. Done? What did you think of to make it happen? If you're like me, all you thought was (in my case), "Jeremy Lewis." I didn't have to think of sending electrical impulses through my nerves to my vocal folds, jaw muscles, and neck muscles. I literally just thought my name and my brain made my body produce the sound. The same thing works for singing, walking, chewing, writing, or any other physical task you want to accomplish. You don't have to think about performing these tasks because your body knows how to do them. Next time you want to think about the mechanics of playing remind yourself that your brain will take care of the hard part. There's no need to introduce complexity to a situation that your body can handle on its own. Thank you for reading! |

AuthorJeremy is Associate Professor of Tuba and Euphonium at West Texas A&M University. |