TuBlog |

|

|

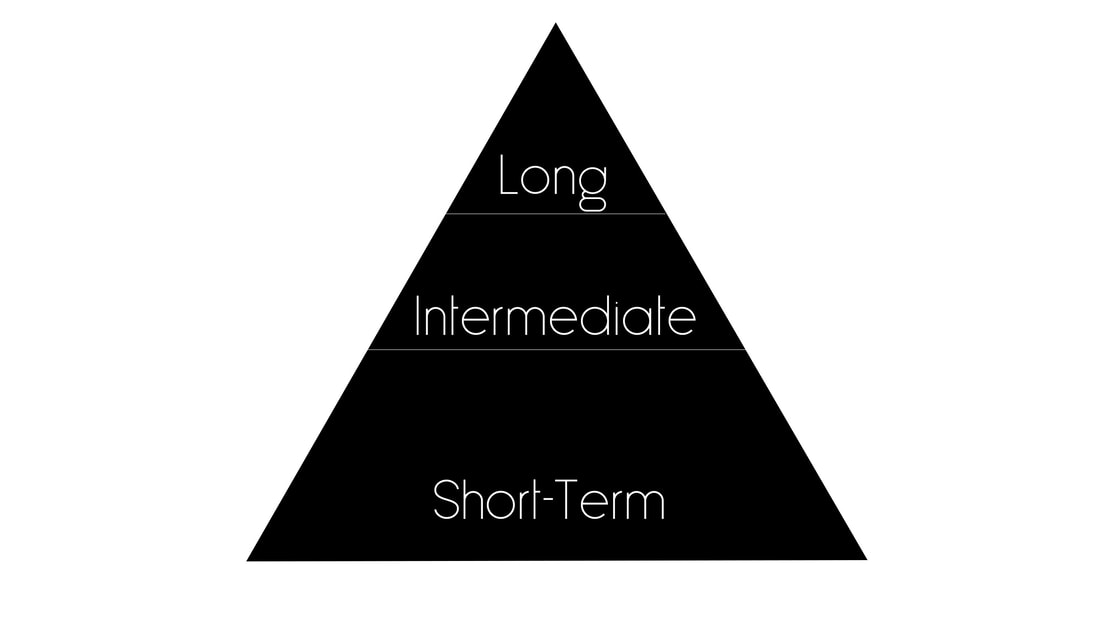

I've mentioned before that I'm a very goal-oriented person. I believe that the right set of goals helps me stay focused and centered on the tasks that I need to accomplish. The most effective goals fall into three categories: Short-Term, Intermediate, and Long-Term. Each of the short-term goals feed into your intermediate, and the intermediate into the long-term goals. Short Term Goals I like to think of goals as a pyramid shape. The base of the pyramid is made up of short term goals. These are goals like “Today I’m going to increase the tempo on ScEx 2 from 80 to 90 beats per minute.” Or, “I’m going to find a way to hit the high E in the Gregson Concerto before Friday this week.” Short term goals tend to be on the scale of days or weeks. They also may seem insignificant, but they can really begin to accumulate over time. Imagine where you'd be if you set a short-term goal of increasing the tempo of a double tonguing exercise by two beats every day. How far could you get in a month or a year? You should have many short term goals, maybe three for each intermediate goal. Every short-term goal should feed into the next level of the pyramid. Intermediate goals The middle section of the pyramid is made up of intermediate goals. These are goals that you'll need to work toward spanning a time frame from a month to a year before they can be accomplished. My primary intermediate goal right now is this: "Before July 4th I'm going to be able to play ScEx 1-3 smoothly, with no gaps/breaks at 160 BPM at any dynamic level from pianissimo-fortissimo." Here's another example: "Before June 17th I'm going to have three episodes for TuVlog ready for release on YouTube." You should have fewer intermediate goals and like short term goals, they should also feed into the next level of the pyramid. Long term goals Long term goals are achieved over the course of years or your entire lifetime. What are the things you want to accomplish by the end of your life? An example of a good long term goal for me is, "I will be Full Professor by the time I turn 40 years old." Another example for a younger person is. "I will graduate with my Doctorate in Tuba Performance with a 4.0 GPA in two years." Long term goals take enough of an investment of time that you should only have a few. Any more than five or so and you risk your ability to accomplish the goals due to lack of focus. So pick just a few that you’re sure are worthy of your time. Also consider that you want the long-term goals to be as challenging as possible, while remaining realistically achievable. Notice that every level of the pyramid feeds into the step above it. Short-Intermediate-Long. The base of the pyramid is broad, with lots of short term goals. The top of the pyramid is narrow. So there's only room for a few long term goals. Bill Gates says, "Most people overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years." SMART Goals

One thing to keep in mind about goal-setting is that goals aren't effective unless they have certain characteristics. Remember the acronym SMART. If you need to, go back and read the goals I used as examples above. They all follow SMART goal-setting characteristics. They are Specific. Each goal is detailed enough that it doesn’t need further clarification to be identified or understood. They are Measurable. Progress toward all of the goals can be tracked and quantified over time. They are all Attainable. Each of these goals is something I personally am capable of accomplishing. They are Relevant. Every one of the goals is something I'm interested in or is closely connected to things I'm currently working towards. Finally, they are Timely. Each of the goals has an associated date by which to be accomplished. If goals lack any of the SMART characteristics it means you'll be less likely to follow through or complete them. Think of it this way. Someone may say, "I want to be the best ever." This isn't specific. What area do you want to be the best ever in? It isn't measurable. It's not really possible to measure a goal like this, especially when it isn’t clearly defined. It's not really clear whether the goal is attainable, relevant, or timely either since it lacks specificity. Even a goal such as, "I want to be the best tuba player ever by the time I retire." doesn’t work because there are still questions that must be answered about it before it satisfies all the SMART criteria. Specific: How do you define "best tuba player ever"? Measurable: How are you going to tell when you are the best ever? Attainable: Only one person can be the best ever at something, are you able to do this? Relevant: Are you a tuba player now? Timely: When will you retire? Hopefully, some of this resonates with you. I've used this procedure for years at this point and think it works well. Happy practicing!

0 Comments

Last summer I wrote about focusing on a single goal and going all-in on a single weakness in my playing over the summer break. You can read about it here. That approach was effective, so I'll do it again this summer, but with a few tweaks. This summer I'll be focused on a single goal (moving in and through the top of the staff), but I'll have other tasks as well. I've already planned-out what repertoire I'll be performing next Fall. While I won't start working on the repertoire until July, I've planned out the means by which I'll improve my playing in order to better execute the repertoire when it comes time to perform.

Here's what I did. Once I'd chosen the solos I'd perform on my next recital I looked through them and considered what techniques and skills each piece would require. The idea is that in an ideal world you should always have more of said skill than is required for the given piece. In other words, your performance skills (or lack thereof) should never govern how the piece is performed. This requires an awareness of your deficiencies as a player, the challenges of a piece of music relative to those deficiencies, and how to go about improving those deficiencies. This is a topic that's been an interest of mine for a while. I even wrote my doctoral project over similar subject. You can read it here. Here's an example: technical pieces like Carnival of Venice are often performed with the theme at the written tempo and the variations (especially the final variation) at a slower tempo. This usually happens because the player lacks the requisite skill to perform the whole piece at the full tempo. In this case the technique in question is finger speed, coordination, and dexterity. Next year I'll be performing Metallic Figures by Kevin Day. Here's the protocol I developed to get myself ready to perform it. I've listed each movement and the challenges associated with each as well as some general challenges that apply to the whole piece.

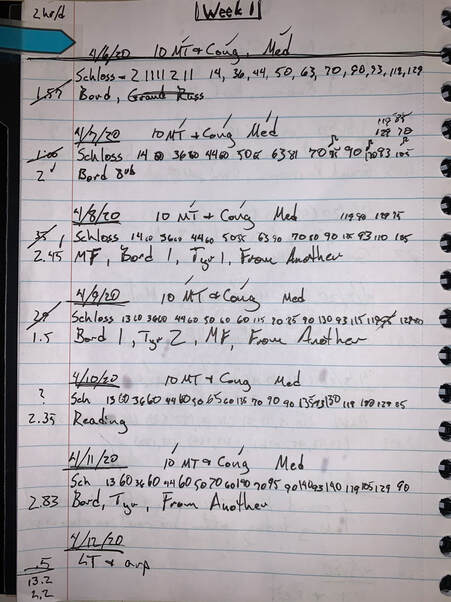

The reason for Loud Playing is that I'll be performing the piece with the band. Playing solo over is generally extremely demanding in terms of volume of sound. It's one soloist against 50-80 band-members. It's sort of like how you play louder with an accompanist than you do in the practice room, but way worse! I've done that for each of the pieces I'll perform on my recital in the Fall. I've started working on them every day which is the bulk of my practice after completing my routine. There's a lot to cover, so I try to hit everything at least once a week. I'd like to know what you're working on this summer. Leave a note in the comments below. Thank you for reading and happy practicing!  I've mentioned in past posts that I keep a practice journal. There are many benefits to practice journaling. You can see the progress you're making, you can look at what you've been spending the most time working on, it makes it easier to plan what to work on, it makes it easier to diagnose problems with fatigue, and the list goes on. I recommend that all my students keep a practice journal. For this post I've included pictures of my practice journal in the three main sections in it. I'll go over exactly what I keep track of in each section and the various elements of each. Section 1: Daily Log In section 1 I keep track of the things I do in my daily practice sessions. There are several elements I like to track from one day to the next:

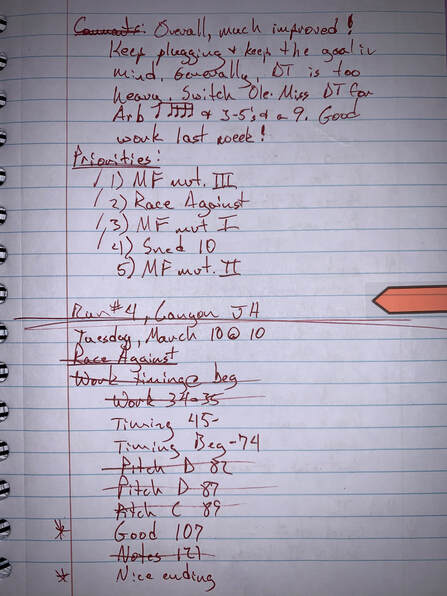

Section 2: Listening Commentary Any time I do a run-through I record it, listen back to it, and take notes over what I hear. It's a great way to teach yourself! The picture here is of the last page of the commentary for my third run-through and the first page for the commentary from my fourth run-through. I'll go over this page from top to bottom.

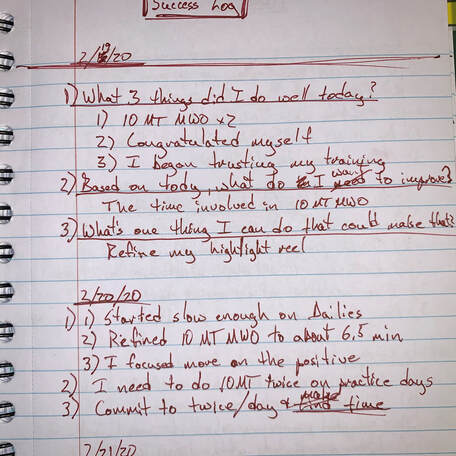

Section 3: Success Log The Success Log is something I started doing recently. It's a great way to end a practice session on a positive note. It's pretty simple, but often not as easy as it seems it should be. It's also pretty self-explanatory.

I experimented at one point with using an Excel spreadsheet, but there's just something I like about having a handwritten journal that I enjoy more than tracking in a spreadsheet. Using some form of electronic journal is fine as long as it works for you. I like that I can hold my journal in my hands and that it's ready to accept or display data as soon as I pick it up, no searching necessary. As I mentioned above, there are many benefits to using a journal. You can use as many or as few of the elements I listed. Journaling is a great way to make your practice more effective, efficient, and deliberate. Happy journaling! When brass players attempt to think about the way to move their body as they play, they become overwhelmed in trying to consciously control the cripplingly complex entity that is the human body. This is known as paralysis by analysis and is documented as far back as Aesop's Fables. Try this: describe, in detail, every single body movement required to shoot a basketball through a basketball hoop. Or, try to shoot a basket by thinking of each step involved.

Here's a taste of the complexity involved in such an action. First, you have to jump. How do you jump? You forcefully extend your legs. How do you do that? You have to contract your quadriceps, glutes, and calf muscles. Awesome, how do you do that? You have to send a signal from your brain along the specific nerve pathway to the appropriate muscle group...? Sweet, so you know how to consciously send signals through your nerves? No. Oh, okay. The point is, at some point along the way you would have to delve into areas that only the subconscious mind is capable of controlling. The same is true for playing an instrument. So many players, myself included, get caught up in forcing our bodies to work in a way that it isn't inclined to do. We try to consciously control the physical aspects of our performance. We have almost no business in doing so. The single exception I can think of in this case is incorporating a new movement pattern in place of one that is limiting your progress as a performer. I recently came to the realization that this was happening to me as I would play a specific interval during my daily routine. As I attempted to play the interval, I'd think about how to form my embouchure or how to shift. Inevitably, I'd miss the top note of the ascending interval. Then I'd repeat the process of playing the interval until I played it accurately a few times. This cycle repeated itself every day over the course of months or years. I'd try different things at different times. I'd sing, buzz, and then play. I'd transpose the interval to a different range higher and lower. Really the only thing I've found that works reliably is focusing on the sound I want to produce, rather than the exact movement required to produce it. For someone who's been playing a brass instrument this is similar to a movement cue. Movement cues are simple instructions which inspire a specific result in the body. Here's my favorite. When I was learning to squat I had trouble increasing the weight I was lifting beyond a certain point due to lower back pain. My trainer told me that I just needed to engage my hip-rotators. At the time, I had no idea what she meant by "hip-rotators" nor how I was supposed to engage them. Basically, the hip-rotators are a group of muscles around the hip joint that help control how the femur moves and helps protect the spine as you squat with weight on your back. The second trainer had a great movement cue for engaging the hip-rotators: spread the floor apart with your feet as you squat and stand back up. Try it! Put your hands on your hips and try to spread your feet apart. You don't even have to squat to do it. The muscles that flex as you do this are the hip-rotators! You didn't have to think about it at all. You just spread the floor with your feet. That is an effective movement cue. Now, a similar phenomenon needs to happen when you play your instrument. Think of the result you want to achieve, not how to achieve it. You want to play an interval? Hear the interval in your head as clearly as possible as you try to play it. You could even imagine your favorite player and how they would play it. Doing this gets you out of your own way. Here's another example. Say your name out loud. Done? What did you think of to make it happen? If you're like me, all you thought was (in my case), "Jeremy Lewis." I didn't have to think of sending electrical impulses through my nerves to my vocal folds, jaw muscles, and neck muscles. I literally just thought my name and my brain made my body produce the sound. The same thing works for singing, walking, chewing, writing, or any other physical task you want to accomplish. You don't have to think about performing these tasks because your body knows how to do them. Next time you want to think about the mechanics of playing remind yourself that your brain will take care of the hard part. There's no need to introduce complexity to a situation that your body can handle on its own. Thank you for reading! I've written before about daily routines and their importance to the development of every brass player. My stance on that certainly hasn't changed. The daily routine is where the majority of your progress as a brass player will take place. Something I've been experimenting with recently though is the use of multiple routines over the course of a few weeks.

The reason for this experimentation is this: I'd been doing the same routine (Routine III) for a two years. I'd made great progress, become a more complete player, and...reached a point with one of the exercises in particular where I was becoming overly concerned with the mechanical aspects of playing. This is a bad thing. It's called paralysis by analysis. More on that next time. Long story short though, after a certain point you should really only think about what sounds you want to come from the instrument. In any case, I thought Routine III had run it's course for me. So I decided to adopt a new strategy. I'll probably come back to Routine III during my off-season (starting in MAY!). Until then though, I plan to rotate every couple of weeks to a different routine. The performance season is September-May this year. So for what's left of performance season I'll use Daily Fundamentals for the Trumpet by Michael Sachs, The Brass Gym, Daily Drills and Technical Studies for trumpet by Max Schlossberg, and a few others I've found online. I'll let you know what I find out as I go through the process of developing this idea. For the time being, I'm excited to be trying something new because I believe it could yield great results. At the very least, it will help me to stay well-rounded during the performance season. Let me know what you think. Thank you for reading! |

AuthorJeremy is Associate Professor of Tuba and Euphonium at West Texas A&M University. |