TuBlog |

|

|

I do the majority of my practicing in my office at university. There's a busy hallway right outside my door and a window which looks out into the atrium of our main music facility. There are almost always people near enough to my office to hear me practice in real time. I was thinking about this recently and began to wonder who might be listening to my practice sessions from the hallway.

I'm not suggesting that people camp outside my office door and eagerly await the arrival of my first notes every day (as cool as that would be). However, the thought that people walk past my door and hear what I'm working on reminded me of something I've heard a lot of musicians say: always sound your best. The sentiment of always sounding your best is well-intentioned, but impractical and unsustainable. It's also in direct contradiction to one of my axioms, which is that practice is for problems. If you constantly attempt to play your best, you'll be stuck forever playing like you do right now because the fastest way to improve is by attacking your weaknesses. Attacking weaknesses means making mistakes. Making mistakes means sounding less than your best. The goal is to improve every time you sit down to practice. People walking by probably think that I don’t perform as well as I do since I spend most of my time working on weaknesses. They walk by and hear me sounding my worst, precisely because I'm fixing the highest priority problems. I think certain people are surprised when I perform because there’s a big difference between performance preparation (practice) and performance. Performances are a very different product than practice would indicate. This is because I spend so much more time hashing out problems (improving weaknesses) than working on my strengths. Here's another way to look at it: maintain strengths, but focus on weaknesses. Better yet, make weaknesses improve so much that they become strengths. It's best to sound your best in certain situations. Find a way to peak for each performance. If that's not possible, decide which performances are most important to you and peak for those. Ultimately, you’ve got to decide what’s more important to you: improving or sounding your best.

0 Comments

First, Merry Christmas! Second, I've posted a new video on my YouTube Channel. It's Teutonic Tales #1: Damon - Tanz.

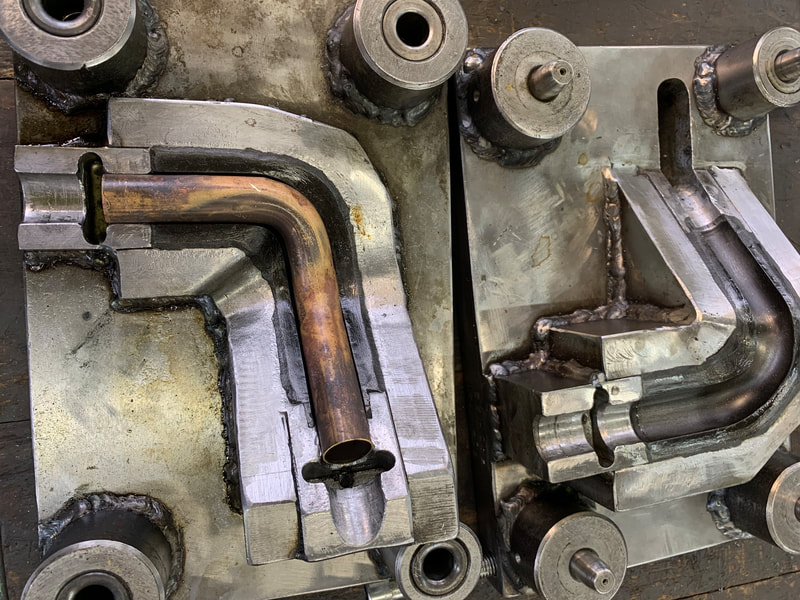

Now for the important stuff! A few weeks ago I had the distinct pleasure of traveling to Waldkraiburg, Germany to visit the Miraphone factory. Christian Niedermaier was kind enough to pick me up at the airport in Munich and drive me to meet with German Tubist, Dirk Hirthe. My purpose for meeting with Dirk was to discuss German tuba philosophy; when and and why they use bass or contrabass tubas. This was an interesting discussion. I learned that German tubist typically play bass tuba (F or E-flat) by default and switch to contrabass (CC or BB-flat) when specified. For those of you who don't know, this is the opposite of what we do here in the states. After meeting with Dirk, Christian took me to the Miraphone factory (picture 1, below). At the factory I tried most of the instruments in the show room (picture 2, below). There were many instruments to choose from, including pretty much all of their inventory. Miraphone starts the manufacturing process with raw materials like brass tubing (picture 3, below) and huge rolls of brass sheet. They make basically everything for all the instruments in the factory. This ensures that all of the materials are of the highest quality. Picture 4 is a picture of a tube after being bent and expanded. There are actually two angles in this one. Once it’s bent it’s put in the steel mold and expanded in a press machine with an oil mixture under extremely high pressure. This tube fits the Petruschka. When I first looked at this part I began to realize just how many steps are involved in going from raw materials to a finished product. There are literally thousands. The process can be loosely broken down into drawing, bending, expanding, spinning, soldering/assembly, polishing, and finishing. In picture 5 on the left are some of the assembled instruments that are awaiting final polishing. In the background on the right are bells. Picture 6 shows a 186 BB-flat tuba being lacquered. It’s in a booth which is designed to minimize the amount of dust and other contaminants in the air from getting in the lacquer. In addition to meeting people from Miraphone and touring the factory, I was there to pick out a new Petruschka F tuba. The one in the show room had a silver finish. I was able to choose between two unfinished Petruschkas. It was a difficult decision because they both played well and were close enough to each other that they were almost indistinguishable. Picture 7 shows the instrument I ultimately chose. Before Miraphone ships it to me they’ll switch-out the leadpipe, add a tuning-slide kicker, add water keys, polish, and silver plate it. I was astonished to learn that about 30% of the manufacturing process is actually polishing the instruments in preparation for the final finish (either lacquer or silver). After the trip, I have a new respect for the quality and skill involved in making a Miraphone instrument. There are about 60 people who work to make instruments in the factory. I saw first-hand that every single one of them are invested in making instruments of the highest quality. So, next time you sit down to practice, take a minute to consider what was involved in producing the instrument in your hand. Thank you for reading! I hope those of you in the U.S. had a great Thanksgiving holiday and are recovering from the food-induced stupor. I recently released a new performance video on my YouTube channel. Here's a link to the new video, The Grumpy Troll.

Thank you all, loyal readers for following the Tuba Tuesday Newsletter. It means a lot to us here at Tuba Central that you continue to read and share the content. I've got big plans for future editions including: my trip to visit the Miraphone factory, two arguments, breathing, and more new videos. So stay tuned! Thank you for reading! This has to be a quick one. I'm leaving for Germany in two hours! (more about that next time)

I've been thinking recently about my purpose, my Why. What is my reason for being on this planet? This question came up at the beginning of the semester. As we were about to start school I was told I would probably have major surgery to alleviate several medical problems which had developed in my body. This raised many questions. Could I give a recital this year? Would I be able to keep playing? Would I survive? I decided I wouldn't let any of the medical issues slow me down. After a somewhat serious procedure and further testing, the medical issues ultimately turned out not to be as serious (or maybe as imminent) as we thought. However, as I was mentally processing this news and dealing with it emotionally, I began to wonder what the point of my existence was. After much reflection, I realized that secondary to caring for and loving my family, I want to be the best tuba player I can possibly be and that I want my students to be the best they can be, too. So I kept thinking about it. Those are worthy aspirations, but they didn't seem to be enough. They seemed to feed toward a larger, more transcendent goal: I want to help popularize our instruments and share them with as many people as will hear them. I later realized that things like practice and getting up early to work are much easier when you can articulate the reasons you're doing them. This helped me to achieve things above and beyond the goals I had set for myself this semester, in spite of an uncertain start. What is your Why? Thank you for reading! |

AuthorJeremy is Associate Professor of Tuba and Euphonium at West Texas A&M University. |