TuBlog |

|

|

Have you ever thought about what sort of training professional athletes go through in order to stay in shape for competition? I first encountered this concept in a book I recently read called 10-Minute Toughness by Jason Selk. I strongly recommend it for anyone looking to develop a yearly practice schedule. just like the astronomical seasons (Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall), there are four: post-season. generalized preparatory, specialized preparation, and the performance season. Each is roughly three months long and has distinct characteristics.

Postseason

I'm going to be doing this cycle for the foreseeable future. I think it's a great idea for advanced performers who need additional structure to their performance planning. This cycle will even factor into my daily routine/warm-up. Side-note: In writing this post I'm assuming that you're a sufficiently advanced player that you'll need an annual cycle. What I meas by this is that intermediate or novice players are (usually) not yet able to practice hard enough to warrant long-term considerations to rest and recovery. I'll use myself as an example. As a player who has developed over the previous twenty-six years, I am able to practice extremely hard six days a week. The seventh day I really need a rest day. Incidentally, that's exactly what I do. Practice six days a week, with a light practice day to recover on the seventh. If I don't rest, it really starts to show. My sound will shrivel, flexibility begins to disappear, and range deteriorates. In fact, there's a significant difference in the way I play mid-week versus the end of the week. For me actively working to increase range during the performance season comes at the expense of repertoire and performance quality. Novice and intermediate players don't need recovery as badly since they are not to the point yet where they can entirely wear themselves out over the course of a week. So for a novice or intermediate player a better strategy would be to keep working on fundamental exercises year-round and work towards daily improvement of skills. So take this into consideration before you adopt an annual Practice cycle. Let me know what you think! Thank you for reading!

0 Comments

Has anyone ever told you that you should try meditation? Cool, I will too.

YOU NEED TO MEDITATE! What do I mean when I say meditate? Meditation is time that you spend trying to quiet your mind. You try to focus on a single thing. I usually focus on my breathing while sitting in a chair. You could also mentally scan your body, or listen to a guided meditation. This type of meditation is basic mindfulness meditation. There are lots of resources online for helping you choose what could be most useful to you. I use mindfulness because seems to be the most useful to me. Here’s my process:

Why Meditation? To me, meditation is the best way to train your mind to focus on what you need to focus on when you want to be focusing on it. There's plenty of research to back this up as well. Basically, it says that meditation is one of the best ways to combat distraction. Some research also says that on average we are distracted every 40 seconds when we work from a computer and it takes us up to 23 minutes to get focused again. Yikes! That means most people spend the majority of their workday either in a distracted state or recovering from it. Why is distraction a bad thing? Distraction slows down practice productivity. Your mind also wants you to be distracted by the symptoms of nervous anxiety when you perform. Why is meditation good for your attention? It lowers the time it takes for you to bounce back from distraction. This will have positive ramifications for more than just practice and performance. When should you meditate? I usually do a quick session of mindfulness meditation before each practice session or performance. This typically happens early in the morning and in the late afternoon or evening. I also tend to cap daily meditation sessions at two. Give mindfulness meditation a try and let me know what you think. Thank you for reading! What do you do when you’ve been rejected? When you’re told what you did wasn’t good enough? When they say someone else was better? What do you do in the face of harsh criticism?

If you want to make a living in the music business, you've got to learn to handle being rejected over and over again. I’m not afraid to say that I have a fair bit of experience dealing with these things. When I’m rejected for an audition or job application, I've learned to view it, even welcome it, as an opportunity to improve. I think to myself, “I'm not going to let this happen again. Next time I come back, I’ll be too good to be ignored.” I use any anger or frustration as a fire that motivates me to buckle down, work even harder to improve, and find the way past the current hurdle. At certain points in my life I've rebounded from a slight or rejection by finding fury. This isn’t the kind of fury that causes people to lash out or get in a fight; this is the simmering, brooding fury that settles in and makes a home in your mind for a while. This is the fury that whispers, "They said you weren't good enough. Will you let that happen next time?" Here's an example: when I was in graduate school at Indiana University, we had auditions every semester for ensemble placement. There were four or five orchestras, three bands, and four big bands. The most coveted positions were in the orchestra, or at least the top band. My second semester I was in the second jazz band. I was last place in that particular audition. I know this because Mr. P left his audition notes out on the table for me to read while I waited for him to start my lesson. I think he did it on purpose because he knew me well enough at that point to understand what it would do for me. I read Mr. P's audition results and at first was hurt. I'm very competitive, and desire to be the best of the best. I also sulked over the dawning realization that I would be spending the next semester in the jazz band (nothing against jazz, but it's not my thing). Most shamefully, I tried to find someone else to blame for this, but couldn’t manage to. It always came back to me. Being last hurt my pride and stung my ego, but I had no one to blame but myself. I was the one who didn't take the audition seriously. I was the one who failed to prepare the repertoire. I was the one who had earned a last place finish. So what happened next, you ask? I practiced, and practiced, and practiced some more. Going to jazz rehearsals was a constant reminder of my own failure to take my job of getting better at tuba seriously. The fury was there and was fueled as I attended orchestra concerts with my peers playing in the ensemble. Before the audition I'd been practicing around two hours a day. That was barely enough for maintenance; I needed to be working on improvement. Clearly I was not in a position to rest on my laurels. That semester I upped my average daily practice time to around five hours. That summer I increased it again. By the time we came back to school in the fall of my second year at IU I was practicing on average forty hours a week. In the first semester of my second year I fared much better, earning one of the top positions and placement in the orchestras. I keep pressing on and working hard because I want to become my best self, the best possible teacher and performer I can be. Here’s what keeps me rolling: I don’t blame anyone else for not noticing my end product. I take total responsibility for it and vow to put in the work so that next time, they will have no choice but to realize how much I’ve improved. Thank you for reading! Have you ever had a performance that you were underwhelmed or even disappointed by?

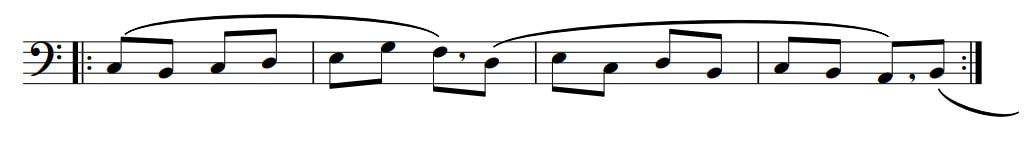

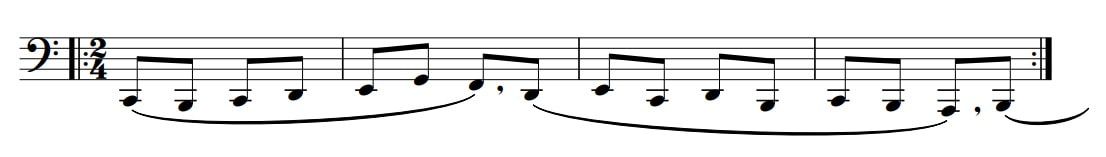

First, after a performance you're unhappy with, ask yourself what went well. Once you've got an answer to that you can proceed. Next, you can move on to addressing problems. Why were you disappointed? For me there are usually two reasons I’m bothered by a performance. Either I allowed my nerves to get the best of me or I was under-prepared. There are simple solutions in both situations. For performance anxiety you basically need to put yourself in situations where you feel pressure while you perform. This primarily means that you need to perform for people. You can also simulate the symptoms of nervous anxiety by doing some jumping jacks, push-ups, jogging in place, etc. this will increase you heart rate, respiration, and probably make you shake a little bit. For under-preparation give yourself more time to learn the repertoire. If you had two months to learn the repertoire last time, try giving yourself three months next time. Or if you had six weeks, give yourself eight. The numbers really aren't the important issue here. Ensuring that you have adequate prep time is. You can also address your practice proficiency. Make sure you’re being honest with yourself when you practice. Never allow mistakes to go unaddressed. Obviously, there are some exceptions to this. You can’t fix every problem right now. Otherwise, we’d all have new repertoire ready for performance by tomorrow! Another consideration for under-preparation is whether or not the piece you performed was within your current capabilities. If not, choose rep that you can handle more readily next time. If the rep was within your current abilities, see above. Later, go over a few things mentally. What could you have done better? Often there are specific problems holding performers back from having a better performance. There are any number of things that may be a culprit here; range, flexibility, articulation, dynamic contrast, musical concept, etc. Figure out what the issue was and how to fix it before your next performance. Add exercises to your routine that will cause you to improve on the identified issue. What were some other potential contributing factors? Distraction? Hunger? Unforeseen hurdles that caused you to show-up late to the performance venue? Not getting time to warm up adequately? All of the above? Ask yourself these questions and find solutions to them. Then get busy working on the problems you’ve identified rather than dwelling on the disappointing performance. You can’t change the past, but you can (and should) learn from it. Use it to your benefit in the future. Awesome! Now you know what you need to work on. So get to it! Thank you for reading! I’ve mentioned before that I’m not a fan of most breathing exercises. The reason for this is that it seems to me that people who do a lot of breathing “calisthenic” type exercises tend to have tight sounds. If you’ve been reading TuBlog for a while you know axiom number two (The Seven Axioms of Teaching) is always play with your best sound. Try this: go back to the beginning of this blog post and read it aloud. What do you notice? Now, if you've got an instrument nearby play something and notice your breathing. How is conversational breathing different from breathing as you play? In a conversation your breathing is shallow, slow, and imprecise. Hopefully, when you play your breathing is deep, full, relaxed, efficient, and exact. A lot of players breathe conversationally as they play. Our breathing should be more like when you’ve been running sprints than conversational. As low brass players, we need to be breath athletes, a virtuoso breather. Breathing in context must be practiced in the same way you practice technical passages of notes. Here’s an exercise that I think is useful. Play it in every key, any range, all dynamic levels, and any tempo. The lower/faster you play it, the more effective the exercise will be. Here are the rules:

Euphonium Tuba Add this exercise to your routine and I think you’ll be pleased with the results. What do you do to work on breathing?

Thanks for reading! |

AuthorJeremy is Associate Professor of Tuba and Euphonium at West Texas A&M University. |